The Transmission Record

Bob Verity

Last updated: 30 Mar 2023

Source:vignettes/transmission_record.Rmd

transmission_record.RmdIn order for a transmission model to plug into the SIMPLEGEN pipeline, it needs to be able to generate a transmission record. This vignette describes the format of the transmission record and explains the logic behind storing information in this way.

What is a transmission record?

When we simulate from a transmission model there are typically many thousands or even millions of events that take place. Some of these events have the potential to impact the genotypes that we see in our final sample of infected people. This does not mean they definitely will impact the observed genotypes, just that that could in theory impact them. A good example is a host being bitten by two infectious mosquitoes; this could result in a polyclonal infection if the mosquitoes carry different genotypes, or it could result in a monoclonal infection if the mosquitoes carry the same genotype.

On the other hand, there are many events that cannot impact the genotypes we see in our final sample. One example would be a human host dying, either as a result of infection or from natural causes. If a host dies then by definition it will not make it into our final sample of malaria-positive people, and so, for our purposes, tracking this event would be a waste of time and computer memory.

The purpose of the transmission record is to keep a record of all events that have the potential to impact the genotypes in the final sample. A secondary aim is to do this in a computationally efficient way, retaining only the minimum information required. A third and final aim is to do this in a simple and flexible way, thereby ensuring that as many models as possible can access the SIMPLEGEN pipeline.

These aims are slightly at odds with one another - there is no single file format that will achieve all three aims perfectly. In choosing the format of the transmission record we have tried to strike a balance that permits reasonably complex models while still keeping file sizes relatively small.

Tracking infections, not genotypes

The transmission record works with infections, defined in this context as a population of parasites passed between human host and mosquito at the point of biting. A single infection can contain multiple genotypes or a single genotype, i.e. it is a lower level of granularity than a genotype. At the same time, an infection is a higher level of granularity than a malaria episode, which could be made up of multiple infection events. We need this middle ground in order capture things like superinfection, which doesn’t necessarily matter from a clinical perspective but can have important consequences for observed genetic variation.

This brings us to an important assumptions of the SIMPLEGEN pipeline:

We assume that the genotypes within an infection have no direct impact on any aspect of transmission.

A classic example would be genotypes separated by neutral mutations, i.e. those that confer no selective advantage to the parasite. In this case the frequencies of the different genotypes will drift up and down, perhaps undergoing strong bottlenecking at times, but crucially the relative frequencies will have no bearing on the overall progression of disease (otherwise they would not be neutral mutations).

We can also think of examples that violate this assumption. We can imagine a model in which a particular allele confers resistance to a commonly used antimalarial drug, thereby increasing the chance that infection persists even after treatment. Here, the presence or absence of the allele directly impacts the progression of the disease, and so we would need to know genotypes at the point of simulating transmission.

Although this assumption limits the kinds of models that can use the SIMPLEGEN pipeline, it does so with good reason. When this assumption is met it means we can separate out the genetic aspect of simulation from the epidemiological aspect, which in turn can have huge benefints in terms of speed and memory requirements. It still leaves the door open to many research and surveillance questions, for example those that rely on patterns of neutral genetic variation.

Working with infection IDs

To make the transmission record we need a way of tracking infections as they are passed between human hosts and mosquitoes. This can be done quite easily by using three different types of IDs:

- Human IDs

- Mosquito IDs

- Infection IDs

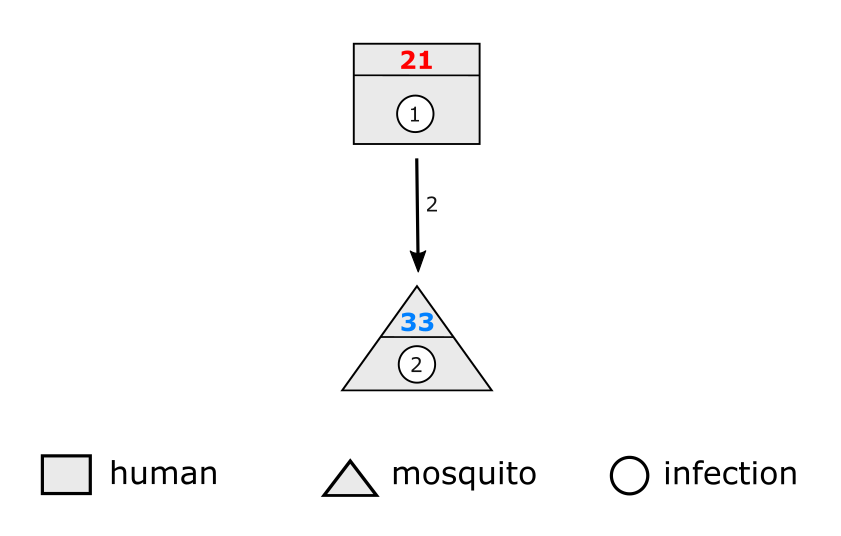

These IDs are nothing more than numbers that uniquely identify a given person/mosquito/infection. Figure 1 gives a diagram of an infection being passed from a human host to a mosquito. The human here has ID 21, the mosquito has ID 33, and the infection IDs are shown inside the small circles. The human host initially carries infection ID 1, which then becomes infection ID 2 when it is passed to the mosquito. We can say that infection 2 is the child of infection 1, and likewise infection 1 is the parent of infection 2. There is nothing special ocurring biologically when we move from infection ID 1 to 2, this is just how we label events.

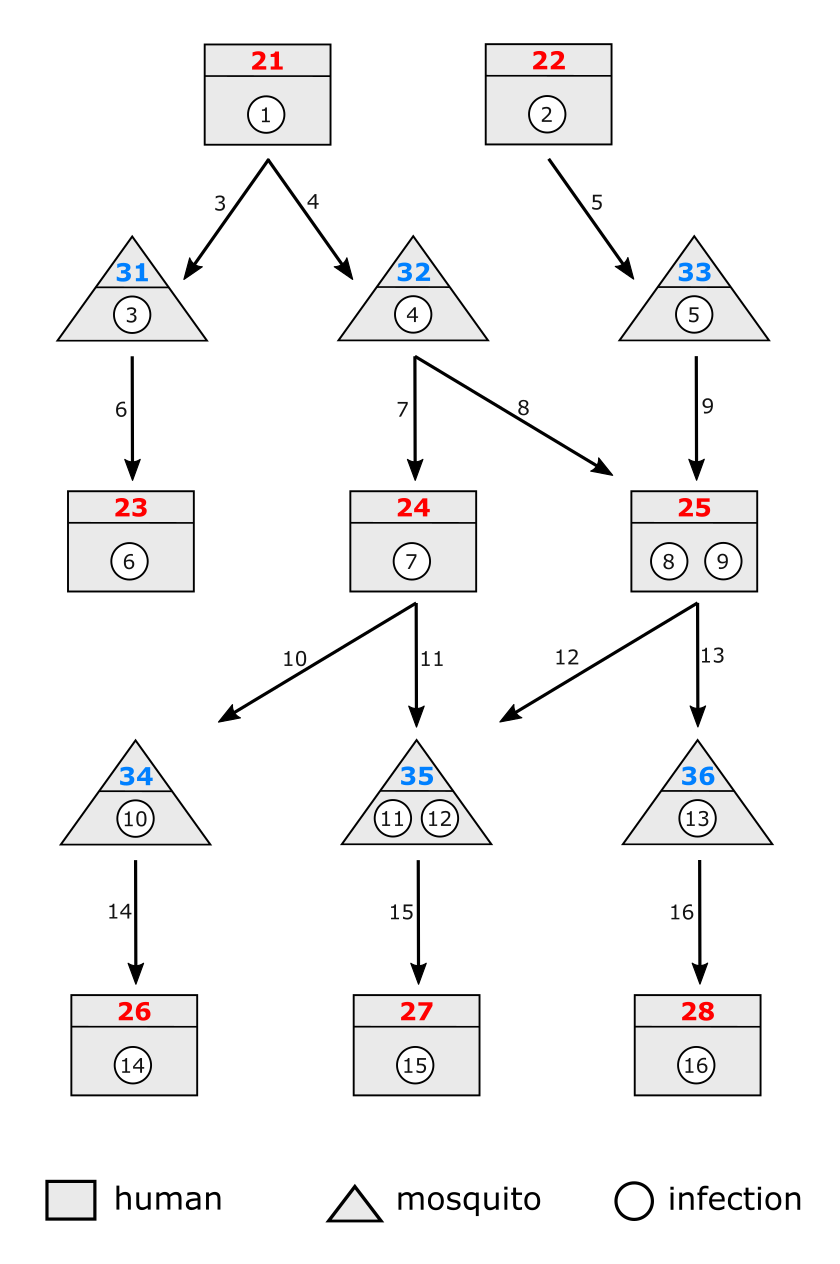

A more complex example is given in Figure 2. Here we have several chains of transmission going between human hosts and mosquitoes.

There are several things to note from this diagram:

Every infection has a unique ID, even infections that are children of the same parent. For example, infections 3 and 4 are both children of infection 1, but they have different IDs to distinguish them from one another (they are different populations of parasites).

Both humans and mosquitoes can be infected multiple times. In this example human 25 picks up infections from two different mosquitoes, and similarly mosquito 35 picks up infections from two different humans. There is no limit imposed by the transmission record on the number of infections a human/mosquito can receive.

An infection can have a single parent or multiple parents. In this example infection 12 is the child of parents 8 and 9. This does not mean anything in terms of genotypes, at this stage we are just tracking which infections were present at the time of the mosquito bite. For example, it might be the case that due to bottlenecking all the genotypes in infection 12 eventualy end up coming from infection 8, but this doesn’t matter to us at this stage.

This method of tracking infections is simple, yet rich enough to capture some important dynamics such as human and mosquito superinfection. It leaves the door open to different types of genetic model later on.

The transmission record

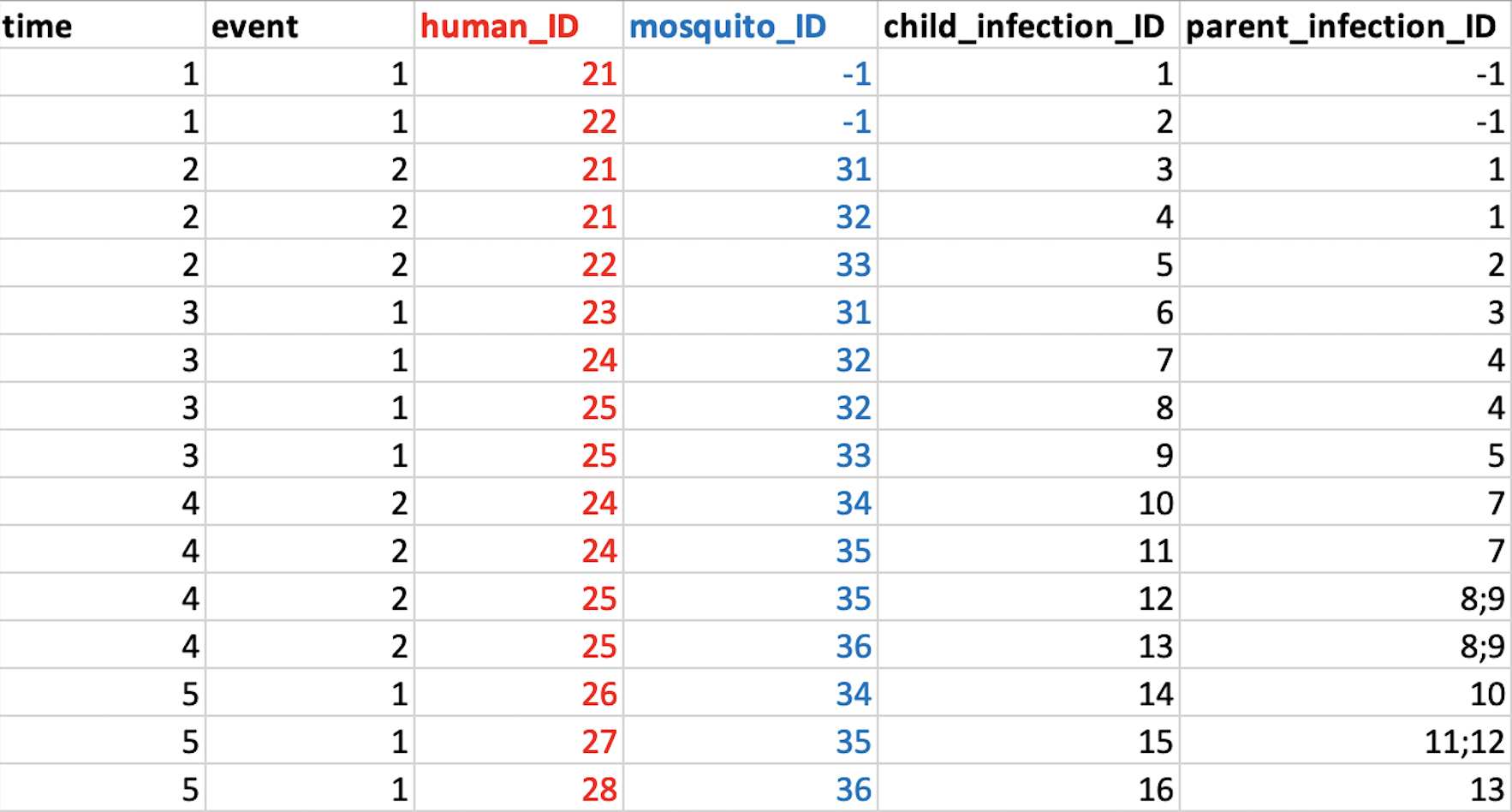

Now that we have established some rules for how infections are passed between humans and mosquitoes, we can think about how to encode this information. Figure 3 gives the exact same information as Figure 2, but in the form of a table:

Again, there a few things to note from this table:

The time column tells us when the infectious bite happened. In this example we have events spread over five sequential days, but there is no need for time to be sequential like this.

The event column tells us whether this row represents a human being infected from a mosquito (event = 1) or a mosquito being infected from a human (event = 2). These are the only two possible events; if we wanted to represent parasites being passed in both directions in a single bite we would need to use two rows.

In some cases we might want to represent a new infection entering the population without a parent; for example an infection imported from outside our study population. In this case a value -1 can be used for both the infection ID and the human/mosquito ID. In the example above we start with two infected humans (21 and 22), and so these are encoded in the table as two new infections without parents.

This is the most basic format of the transmission record. Any simulation model that is capable of producing a record like the one above can plug into the SIMPLEGEN pipeline.

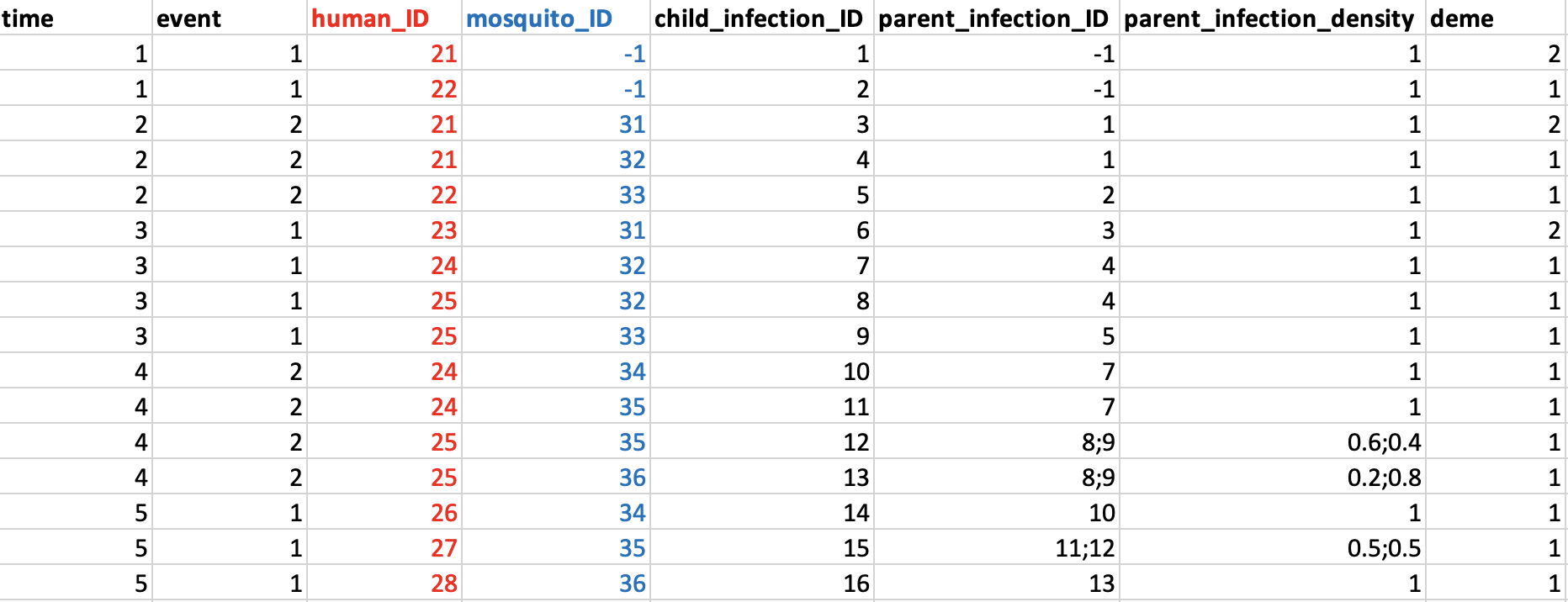

There are also some optional columns that can be used to add depth to the transmission record. The first is a record of parasite densities. In the example above it appears that infections within a host/mosquito are equally important, for example infection IDs 8 and 9 within host 25 are given equal weight, but in reality one of these infections might contribute far more to the total parasite load. We can accommodate this by storing the relative parasite densities of each infection in an additional parent_infection_density column. The values in this column correspond directly to the infections in the parent_infection_ID column, so if there are three values in one column then there must be three values in the other. Some genetic models might make use of this information while others might not.

The second optional field is the deme. This stores the deme (i.e. subpopulation) in which the human and mosquito reside at the time of the bite. For some models this information will be very important, for example if we want to assume some sort of spatial structure in our model with each location having a different mix of starting allele frequencies. Figure 4 gives an example of a transmission record with these optional extra columns:

Some things to note from this table:

Parasite densities are taken as relative values, meaning they can be proportions or absolute numbers.

Demes are integer numbers. In this example host 21 moves demes between their first and second mosquito bite.

The format of the transmission record is a comma-separated file (.csv), meaning it can be opened and browsed manually if needed. The next step in the pipeline will be to prune this record down, which can reduce file sizes dramatically.